By Brentin Mock

On July 7, Memphis passed a resolution declaring racism a public health crisis, following the examples of dozens of cities across the U.S. The city council vote was unanimous. The language of the resolution draws a through-line from the 1866 Memphis Massacre, when white terrorists killed and raped dozens of Black people, to the current Covid-19 pandemic, where the coronavirus has disproportionately infected and killed Black residents, in making the case for a plague of systemic racism.

Among the causes for the declaration, as stated in the resolution: “A failure by any of our citizens to acknowledge the prevalence of racism in our community and to join in the fight to eradicate its effects on the majority of our residents is an unwelcomed option.”

Memphis is now one of more than 50 U.S. cities and counties that have passed legislation declaring racism a public health crisis. The declarations are popping up not just in cities, but also local hospital systems and school districts. They’ve sprouted in big urban centers, but also suburban and exurban municipalities; majority-white cities and majority-minority cities; and, across every region of the U.S. A cluster of small towns and villages in Connecticut has passed them, as has the Douglas County Board of Health in Nebraska.

Pretty much all of them have come in the form of resolutions, proclamations, or some other non-binding document, which leaves open the question of what these declarations will actually accomplish. But for now, these places are on the record stating that racism needs to be treated with the same kind of urgency and resources used for tackling opioid addiction, cigarettes, or, as we’re presently witnessing, the coronavirus pandemic.

Public health science is already solidly behind these efforts, as a number of health leaders and organizations have expressed in their own recent declarations. A June 10 editorial from the New England Journal of Medicine declared that discrimination and racism promote brain disease, “accelerate aging, and impede vascular and renal function,” which produces “disproportionate burdens of disease on black Americans and other minority populations.” The American Public Health Association and American Medical Association have also stated that racism falls within their bailiwicks.

Such journals and professional networks have historically been complicit in making racism a public health crisis in the first place, particularly withthe discrimination and racial fictions they’ve encoded in U.S. health policies. Now they are providing the scientific backing and empirical cover cities need to tackle racism as a policy issue today, even if there is skepticism that these declarations are concrete measures for dismantling it structurally.

“It’s a little thing to declare racism to be a public health crisis, but it’s a stake in the sand,” said former APHA President Camara Phyllis Jones in a recent webinar. “We can develop and disseminate model legislation addressing the many mechanisms of structural racism. In the same way that other groups have modeled legislation to dismantle affirmative action or whatever, we need to develop model legislation for identifying and addressing the mechanisms of structural racism. And we need to disseminate those across local and state governments as well.”

The statements from official health organizations on racism include language about the specific harms of police violence — which the APHA has also designated a public health crisis for Black people. It’s a designation that indicts cities, given that these are the jurisdictions that directly oversee police departments — and the entities usually responsible for paying for police violence. These declarations are springing up right at the intersection of rage against police brutality and a legacy of racist health policies. Both have rendered Black life almost unlivable, and currently under a federal administration that has denied these concerns even exist.

“What hopefully comes with this is access to funding and other opportunities for collaboration. For that, we needed to name it.”

Among governments, Wisconsin is a pioneer of the current approach. In 2017, the Healthiest State Agenda Setting conference, convened by social justice and health equity advocates from across the state, led to the Wisconsin Public Health Association declaring racism a top priority. The association created the Racism is a Public Health Crisis Sign-On petition, which has been adopted by dozens of health organizations and local government bodies, including the Madison Metropolitan School District, the University of Wisconsin, the city of Madison and the city and county of Milwaukee, which were the first local governments in the U.S. to make this declaration last year.

Pittsburgh followed suit, passing a similar resolution in December. While the Wisconsin model focuses almost squarely on racial health disparities, Pittsburgh’s declaration seeks to alleviate the crisis through home ownership, entrepreneurship and employment to improve African-American living conditions. Both Pittsburgh and Milwaukee have been ranked among the worst places to live in the U.S. for Black people. Both cities showcase higher-than-average rates of infant and maternal mortalityfor Black women. The police killing of George Floyd precipitated a wave of other cities passing these resolutions throughout June, with Milwaukee and Pittsburgh as models.

Mayoral supporthas been the norm for almost every city and county that has passed them, according to a CityLab analysis. While local councils are usually the drafters of the legislation, in Charlotte, North Carolina, and Boston, it was the mayors themselves who wrote the proclamations. Boston Mayor Marty Walsh delivered his as an executive order, as did the mayors of Springfield and Holyoke, Massachusetts. The Boston order calls for measures such as “complete and regular availability” of race data on health disparities, and to use that data for analysis of “the complexity of the interconnectedness of societal, environmental, and behavioral factors that contribute to racism.” Walsh directed “every City cabinet, department, agency and office to take all necessary steps to implement” the order, which is among the strictest of the directives passed by other cities and counties.

The notable exception in this mayoral trend is Memphis, one of the few cities if not the only city where residents don’t know where their mayors stands. At the time of publication, Mayor Jim Strickland had not given any public statement for or against the resolution, despite the resolution passing unanimously. Strickland’s office has not responded to CityLab requests for comment.

Memphis, the city where Martin Luther King Jr.was killed fighting for better work conditions for trash collectors, was following the example of the Shelby County Commission, which also approved a resolution on June 22 calling racism a “pandemic.” Notably, the commission’s chair, Mark Billingsley, voted against it, even after the CEOs of three of the region’s hospital systems and the county director of health all made statements identifying racism as a public emergency.

Memphis city councilor Martavius Jones told CityLab that he didn’t expect Strickland to say anything about the resolution and that it didn’t need the mayor’s approval.

“It’s an official statement from the government acknowledging the fact and raising public awareness that racism exists,” said Jones. “So hopefully now actions we take as a city are done with that acknowledgement, pledging to be anti-racist and to affirmatively state that in everything that we do that Black lives matter, whether from a policing or business procurement standpoint, or from a poverty alleviation standpoint. Those are things we need to be conscious about when we function as a city.”

But Shelby County Commissioner Tami Sawyer, author of the county’s resolution, said it’s important for the mayor to respond to the resolutions “to acknowledge Black lives.” Sawyer ran for mayor last year in a controversial campaign that included Memphis Magazine placing what many considered a racist caricature image of her on its cover just before the election. The magazine has since apologized and pulled its print copies from circulation. Sawyer lost with roughly 7% of votes. In her current commissioner role, she says she believes the resolutions can be used as tools for passing racial justice reforms she and her political allies have been trying to get passed for years.

“We’re struggling to get real police reform passed and to get transportation funded, and for our public hospitals, so this should be the lens under which we operate,” Sawyer said. “What hopefully comes with this is access to funding and other opportunities for collaboration, especially around racial co-morbidities and mental health and things that are needed in the Black community. So for that, we needed to name it.”

Sawyer said after the resolution passed, her father, “a political curmudgeon,” texted her a heart emoji with the message, “Thank you, commissioner,” which she took as a sign that it could inspire even those who aren’t the most politically engaged.

“That meant a lot to me,” Sawyer said, “so now we have to do something with it and I plan to do it.”

— With assistance by Kara Harris

Original article was published here.

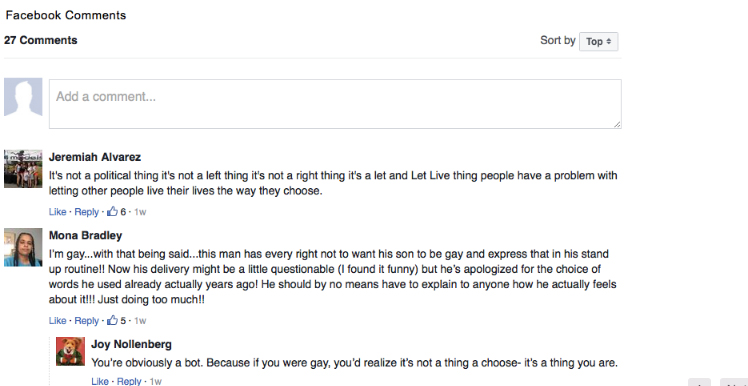

Facebook Comments